|

| View the game like this to make sense of the tactical ideas. |

When it comes to completely different footballing philosophies, we can look to the epic Champions League semi final of Inter Milan versus Barcelona in 2010. For Guardiola, the idea is that if you keep the ball, you control the game. For Mourinho, the idea is that if you have the ball, you can make mistakes. These are the absolutes. This demonstrates two sides of the same coin. How could one incredibly successful manager want the ball, and another incredibly successful manager not want the ball?

If we examine the two statements, we'll realise it's more like a spectrum. If you control the ball, you control the game - not exactly true if the opposition plays a very effective high pressure system. Your pressure is how you can manipulate the opponents while out of possession. Since there are very few moments of true possession within a game, the team with the ball can always be manipulated by the team without the ball. True possession is completely uncontested possession. It's when the ball cannot legally be stolen, such as restarts, and the ball being in the keeper's hands. Even then, the ball carrier can still be manipulated through means of denying space and preventing certain passing options.

Conversely, if you do not have the ball, you cannot make mistakes, is kind of true depending upon how you determine mistakes. Sure, you can't pass the ball dangerously across your own goal and give it away to the unmarked opposition centre forward, if you don't have the ball. The ultimate defensive performance, with a low block and eleven men behind the ball, would ideally mean the game finishes 0-0, and neither team would have a shot on target. Any interception is hoofed swiftly up field. All the time the ball is in the air, it cannot be manipulated by the opposition. It's essentially dead or wasted time. When the ball comes down, it can be contested by whoever is around the landing site.

Shakhtar Donestsk coach Miguel Cardoso presenting for the NSCAA.

Think of a very long ball team that relies heavily on set-pieces. The ball will spend several minutes throughout the game in the air, meaning it belongs to neither team. Dead possession. If you rely on set-pieces for goals, any throw, corner, or deep free-kick will require longer to organise your team effectively. It's these moments, where a team has true possession. Rory Delap drying the ball while Stoke arrange themselves in the box is true possession. At that moment, the opposition cannot do anything, but wait for the ball to re-enter play, where it can be contested. Following that comes a series of knock-downs and 50/50 battles. You'd imagine the team more adept at long ball will win more of those than their opponents. Like Stoke v Arsenal. Or Blackburn v Arsenal. Or Bolton v Arsenal. Arsenal would far out-match their opponents in speed, talent, and attacking organisation from open play. You nullify that threat by keeping the ball in the air, utilising moments of true possession, and, a tactic loved by South Americans that have their goalkeepers take free-kicks (and Spanish teams using tactical fouling) if under threat from a counter-attack, you make an innocuous foul. The referee is less likely to award a yellow card to a player if the foul is not reckless and committed very far from goal. You've sent your hulking defence up for the corner, the ball has been cleared, Arsenal now start the counter, one of your strikers trips the player on the ball, free-kick is awarded eighty yards from goal, and the game pauses for around five to ten seconds, enough for the brutes to regain defensive organisation deep in their own half.

Teams hate playing against a well organised high press. They also hate playing against a well organised low press. Again, it happened to Barcelona in 2012 when they lost to Chelsea in the Champions League semi final. Sure, there was a lot of luck involved in that game, as there was for Mourinho's Inter two years earlier. What's frustrating about a low block, or a team that has parked the bus, is that players restrict space in the dangerous central areas. Zone 14 is a war zone. Opponents are not allowed in there. The front players come back into their own half and press only from halfspace to halfspace, meaning that the opposition has to do a full switch in an attempt to tilt the defence. It's easier to recover from a wing to wing switch than an HS to HS switch if you have perhaps two banks of four on the edge of your box, no wider than your box. With eleven players behind the ball denying all inroads centrally, the defending team is almost impossible to break down. Attacking teams rely so much on prodding and probing with their build-up play, but cannot break down the defence due to their numbers, positioning, and denial of space in key areas. What does the defending team do when they win the ball? Launch it. High, far, deep into the opposition's half. They might not even chase it. That means valuable seconds are wasted when the ball is high in the area. More valuable seconds are wasted when the attacking team needs to go back, collect the ball, and begin their build-up play all over again.

Does this mean mistakes can't be made out of possession? Of course not. Goals are scored because of mistakes. Sometimes they are easier to identify. I like to point out to attacking players that always blame the defence how it was actually their poor cross, or selfish dribble, that lead to the turnover, that lead to the counter, that lead to the goal. Or if the opposition right back overlaps the right winger to whip in a cross that's headed into the net. Could the keeper have saved it? Could the central defender have challenged better for the header? Or was the left winger being lazy, and not tracking back, which allowed the opposition right winger to overlap and easily isolate the defending left back in a 2v1, meaning they could hit in that cross perfectly as it was not pressed?

Whichever method of attack or defence a team chooses to use, you must first consider the following factors; do you have the players to perform it effectively? Will it be an effective counter-measure against the opposition? Do you have the level of organisation required? You're playing Arsenal this weekend and reckon that a high press is the way to go. Are your players fit enough and intelligent enough to pull off a high press? Will a high press actually work against Arsenal? Do you have enough training or video sessions to be confident in your collective ability to perform it this weekend without mistakes? Any kind of decision in football managing is a guess. More often than not it's an educated guess, but the future is hard to predict, and as I've discussed before, football is incredibly random. You could get it right for eighty nine minutes, but that one minute you get it wrong is the minute that loses the game.

So where does this six seconds come into it? These are the six seconds following a transition. A team in possession is in their offensive shape, while the team out of possession is in their defensive shape. Offensive shape is dispersed, with low horizontal and vertical compactness. Defensive shape is contracted, with high horizontal and vertical compactness. The defending team wants to become narrow and deep as quick as possible, providing less gaps within the units, and smaller pockets between the units. Therefore, the attacking team, if they could choose, would like to attack against a team that is much more spread out. It's not American football. There are no downs or timeouts. A team does not get to reorganise after every play. It relies so much on intelligence, discipline, and awareness. Spur of the moment decisions that can alter the course of history. If you intercept the ball, right there and then, it that moment, you now become the attacking team, and the defending team is still in their offensive shape. They are at their most vulnerable in terms of structural integrity at that precise moment.

Why don't more teams make use of this? It's because while the team that lost possession is changing from offensive to defensive shape, the team that won possession is changing from defensive to offensive shape.

The important players in the above picture have been highlighted in red. The yellow CM gives the ball away, the blue CB has intercepted and played forward to the Blue CAM. The dashed arrows indicate the direction the players off the ball will now move as the teams switch offensive/defensive shape. The blues are now looking to get on the outside of the yellows, and the yellows are looking to get on the inside of the blues. Two sides of marking; ballside, which is between the opponent and the ball, and goalside, which is between the opponent and the goal. Notice how the yellow CM , upon realising the negative transition, moves to become goalside of the blue CAM? That's to deny his path to goal. On either flank, the yellow wing players look to become ballside of their blue opponents. And thus, the concept of transition is explained.

If you're not on the Coaching Manual, be on the Coaching Manual.

Another good YouTube follow.

Many coaches will know the feeling of "Well we looked good in training." Often true. Take any wave practice, phase of play, function, pattern drill. Most of the time we find a clear beginning and end of the sequence. You set up a team to either attack or defend, and then coach one of them to do their job more effectively, Let's take the example of playing out from the back. The GK has the ball, you tell your CBs to go to the corners of the penalty box, RB+LB to be on the touchlines, and CMs to rotate and receive on the edge of the box. Maybe even tell the GK to put the ball in the middle of the six yard line rather than on a corner. Ask your GK, can you play a short pass to an available player? Can you clip it into the wide areas? Basic shape and patterns are understood. There may be opposition added in to show realistic distances and angles. The opposition may even sit back and not press high (is this realistic?), thus allowing the playing out from the back to be easier. What does the team do when they have it? They try to run it into an end zone beyond the halfway line. Following that, everyone goes back to their start positions, and the process happens again. The opposition may be instructed to try and steal the ball and to score a goal. The ball goes out of play, in the goal, in the end zone, and we start the practice yet again from the GK taking a goal kick.

Playing out from the back would also involve live possession, such as receiving a backpass, saving a shot, or claiming a cross. Then what? You'd try to counter against a retreating team. Offensive/defensive shapes change. You have the realistic chaos of a game going on all around you. Every time something goes wrong in training, we stop, and go back, and do it again. The opposition team can easily feel neglected or non-incentivised. Like when working with the attacking team to score from crosses, the defending team actually need a way to score, rather than just the job of blocking the cross. Cross comes in, defence heads it away. Then what? We stop and go back to the start. In a real game, the knock-down would be contested on the edge of the box. In this moment, players on both sides are scrambling for the ball. There's been a transition, How can we exploit or deny space?

This is why teams look great in training. They are often doing what the coach is asking and performing very well against conditions set. We're sometimes biased towards ensuring success, or blind towards devaluing the realism of the session. Teams are great at defending in defending exercises, and great at attacking in attacking exercises. What about if the exercise is both? If there's a transitional element to it, suddenly we're in business. It's become realistic. Both teams are motivated to compete due to the incentivisation of being able to score points. You may manipulate the space, the numbers, the quality, the conditions to force certain outcomes, but there needs to be a transitional element and a way of scoring.

Have a look at this simple exercise. Is it incentivised for both teams? Absolutely. Both teams have a way of scoring a point. Is there a transitional element? Absolutely, as two teams are competing for possession of the ball. It's 11v4, so it seems like it's unfair against the 4, but then the 11 are conditioned to just one touch, which kind of levels up the playing field a bit. The pitch isn't huge, which means two things; the 11 can't spread out so far that they can pass it round the 4 without them being able to press. Also, because of the size of it, you could probably shoot from anywhere. This means both teams will have to be quick to press to prevent a first time shot from going over everyone.

If using this session, which topic would you be coaching? For the blues, it could be one touch passing, rotation, combinations. For the oranges, it could be high press, counter-attack. Both sides of the attacking v defending spectrum provide endless possibilities. Another thing that's key is that it allows for switch of play. Too often we set up out sessions in away that don't always allow for large disorganisation of the defence. The blue on the ball is able to play a diagonal pass. That benefits the blues if they are working on support play, combinations etc. and benefits the oranges as they now have to drop, slide, and reorganise their defensive shape to deal with the gained territory of the blues.

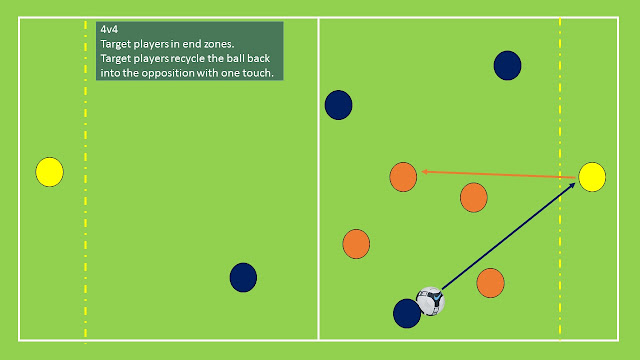

In this above drill, at both ends, there is a target player. The teams must pass it into their target to score a point, who then immediately gives it back into the opposition. The blues are in offensive shape, and the oranges are in defensive shape. The team that reacts to that change more effectively is the one that will prevail from the chaos that is about to ensue. I often tell that player, the magic man or the commedin, that they are a CB for one team and a CF for the other team. Relate this to a game, and we see the blue RM trying a forward pass, that is cut out by the orange CB, and then played into the orange RM. It has to be a one touch recycle because it needs to be fast. If the pass is of lower quality due to the quickness, then that presents an opportunity for the blues to press the oranges while they transition from offensive to defensive shape. Both teams can score, both teams experience transition, both teams can switch play, and the area plus conditions force certain outcomes. You then coach what you see.

The above is an example of how we can really apply aforementioned principles to an exercise. It's very specific. You can easily adapt it so many ways. I intend to discuss the concept of teaching games for understanding in a future piece. This game is an absolute favourite of the players that have played it. It's winner stays on, which keeps things fresh as there is always a chance for revenge or redemption, with the dynamics of the opposition and the stakes always changing. Challenge teams to go on a winning streak. Is there a way to score for both teams? Yes. Even the yellows can score, which keeps them even more interested. They know they can get into the game following a goal, so will work very hard to get themselves into situations to score or assist goals. There's a transitional element with the central area being limited to one-touch. That makes the passing sometimes more ballistic as players can't take a controlling or a correction touch. That entices the opposition to press, despite technically being overloaded 8v4. There's always an option to recycle or switch play, and penetrate via diagonals. This creates scenarios where defences are tilted or stretched, and have to reorganised.

Is this a finishing drill? A passing drill? A defending drill? Actually it's everything. Let's say I choose finishing. We're looking at one touch finishes, and there will be plenty of live examples for this to happen, and none of them will be the same. While I step in to coach my players on finishing, all around me they are working on chance creation and chance denial. Every other aspect of the game is happening right in front of us, which makes it realistic to the game of football, but as coach, I only care about the aspect of finishing. We call that the "hidden curriculum."

In practice we talk about constant or variable. Constant means repetition, variable means random. For mastery, we need repetition. For realism, we need random. The basic shooting drill of players lining up to take a shot, one at a time, is constant. The same thing over and over again. Playing a simple 11v11 match is variable. Anything can happen at any time, such is the randomness of the real game. As a coach, you have to provide repetition without losing the realism. That's why exercises like this are so important when it comes to training, as the organisation and the conditions are what manipulate the exercise to provide the repetition.

But what is so important about these six seconds? It takes about that long for a team to get back into a good defensive shape. The attacking team will not wait for their opponents to be strong before beginning their attack. They will go for the jugular when they are at their most vulnerable.

I will try to explain using a 7v7 for simplicity. The yellow CM tries a forward pass to the CF to receive behind the defence. The blue LB steps in and intercepts the ball. As the CF was running behind the blue defence, it will take him a couple of seconds to recover to be goalside. Currently, there is no pressure on the blue CB, who is able to play forward unopposed. I'm definitely oversimplifying a very complex situation with countless possibilities here, but for a moment follow this train of thought. The blue LM is unmarked and has an unobstructed route to goal. The Blue LB plays to his feet, and he is able to drive at goal. That red mess is the passing lane. The yellow RM should try to block that passing lane if possible. If the blue LM is asking for the ball to feet, then the yellow CM can maybe nip across into the passing lane and steal the ball. It's got to be quick, as the blue LB may only need one or two touches. If either the yellow RM or CM can screen that passing lane, they could prevent that forward pass, thus delaying the blues from gaining territory with the first pass following the yellows losing possession.

The other yellows need to recover, including their two defenders. If that first pass goes through quickly to the blue LM, it may be too late for the yellow defenders to recover into positions that can affect the play. Imagine individual stats, like on a FIFA player card. The yellow RM has: Tackling 88, Awareness 82, Speed 91, Acceleration 90, to name but a few. These are impressive stats that would make it seem quite likely that the player would be able to react in time, is fast enough to recover, and strong enough to challenge for the ball. If he just... doesn't do that... then his stats are irrelevant. Some of it can be down to not being able to read the game quick enough, sometimes slow reactions, mental tiredness, and even sometimes, it's simply that players can't be bothered, or that they don't see the value. An effective pressure system, high or low, requires everyone working hard, doing the same thing. If the yellow LM cannot be bothered to recover to a position to prevent the pass, or even prevent the turn, he does not buy his teammates in defence enough time to recover to positions to prevent that blue CF going direct to goal.

Take it one step further. The blue CF receives the ball, is not prevented from turning, and proceeds along the blue dashed line towards the goal. He is pursued by the yellow RB and CM. His space and time is being greatly reduced by the millisecond as he now faces a 1v2. His teammate, the blue CF, has been keeping up with play and is approaching the edge of the box, hoping his teammate can lay a square pass to put him through on goal. He should be certain to score if 1v1 against the keeper. The one player that can catch him is the yellow LB, but he's frustrated that the yellow CM has given the ball away YET AGAIN BLOODY HELL!!! As annoying as it is, his mistake is our mistake, such is the nature of the team sport. He could choose to have a moment to himself before beginning the recovery. He could then identify that the blue LM approaching the goal is being closed down and now faces a 1v2. What's the point of sprinting back to defend when your teammates should be able to handle the situation? Turns out they didn't handle it, and the ball has been laid off to the blue CF on the edge of the box, unmarked. Who should have been there? This guy. The yellow LB that was frustrated at his CM, and thought the other guys could handle the situation. He took a lazy gamble and lost. It wasn't his fault the misplaced pass was sloppy. It wasn't his fault his two moron teammates couldn't tackle the player on his own. But who will we point to for leaving the striker unmarked on the edge of the box? The player, that for whatever reason, was too slow to recover in those moments following the transition.

At the top level, 11v11 game, it's around six seconds, which is around four passes. It's to do with the probability of scoring a goal following transition. The ball is given away, and the team now on the attack has a strong chance of scoring a goal with the first two passes. Pass three and four are still relatively high, but after pass four, the probability of scoring drops, and then starts to rise again after pass seven. Simply put, it takes six seconds for the newly defending team to adapt their shape and organise. Once organised, they become difficult to score against, so after those six seconds, or four passes, the chances of the attacking team scoring drop. Why the probability of scoring goes back up after seven passes is because the team in possession will have switched the play and begun attacking down the other wing. They have tilted the defence, and caused new confusion and disorganisation. We call it changing the point of attack. I would point out that we can refer to it as a synthesised transition.

For some brief analysis, here are the top ten goals from the recent Euro 2016 tournament. Enjoy.

Lukaku: Belgium v Ireland - 2 passes.

Hazard: Belgium v Hungary - 3 passes.

Ronaldo: Portugal v Wales - 2 passes.

Griezmann: France v Iceland - 4* passes.

Eder: Portugal v France - 1 pass.

Ronaldo: Portugal v Hungary - 4* passes.

Hamsik: Slovakia v Russia - 1 pass.

Payet: France v Romania - 4* passes.

Robson-Kanu: Wales v Belgium - 2* passes.

Shaqiri: Switzerland v Poland - 0** passes.

* means that replays and match reports went no further than that pass. It's difficult for me to ascertain with incomplete data the exact number of passes that were made following transition.

** technically this is correct, as the ball to Shaqiri would be categorised as a knock-down, and he won the second ball. There were, however, four passes in the build-up that lead to the cross.

Still, it gives us a good idea of how long it takes to score a goal. Literally seconds. Data shows that in any given game, a goal is no more likely in any given second depending upon the score. What we do know is that it is more likely that goals will come in the last fifteen minutes of each half, but this does not depend on the score. Just because a team is winning 2-0 with ten minutes remaining doesn't mean that it will finish 3-0 or 2-1. When goals occur is completely random, as it's six seconds that can follow a transition at any given moment.

What's also interesting to note is that Hamsik's goal, although from a corner, was actually a short corner. In modern football, corners have no relation to goals. Some teams may be more adept at set-pieces, and so will, as a team, have a higher proportion of their goals coming from corners. These teams will usually have forced many corners throughout that game, aiding to the likelihood that they will eventually score from one of them. Quantity rather than quality. The same with shots too. I often hear people associated with the side that is losing saying "We need to take more shots." Shots don't necessarily mean more goals. Sure, if we remove most of the variables, we can determine which team has better shooters, or which striker is a better shooter but that's not the case. We need to consider; weak foot or strong foot, strength of the shooter, accuracy of the shooter, distance to goal, angle to goal, pressure or no pressure, direction of pressure, congestion in the way, quality of the goalkeeper, positioning of the goalkeeper, and many, many more. "We get to the edge of the box and we just don't shoot!" Perhaps it's not the right time to shoot. It's not more shots, it's quality of scoring chances. If you keep shooting from thirty yards, you may not score once. Ten shots from outside the box, even if they are on target, is not the same as one shot from ten yards out.

Another thing, something I don't like, is how this information is often neglected in replays, highlights, and match reports. I did extensive searches, and all the highlights I could find of the goals noted with * started with the scoring team in possession. We don't know how they won the ball. The match reports are worse. This guy passed to that guy. But where? How? Who gave him the ball? We see one team attacking, and one team defending. What about the transition? We need to know because clearly it is undervalued. It doesn't enter our collective football understanding. The game is all about who controls the transition.

That one time Blackburn looked like Barcelona.

In the above video, Rovers did start out long ball, but they also changed the point of attack a few times, thus disrupting the organisation of Derby's defence. Through intricate play in the central area, they were able to unlock the defence and score. Twenty five passes, with multiple switches of play.

The many times Barcelona looked like Blackburn.

Defenders may be able to defend, but if there is not adequate recovery from those in midfield, or if the attack decides not to press following the transition, a team can be screwed. It's just chaos. Let's not always blame lack of pressure i.e. preventing or delaying the forward pass. Some players are careless with the ball, and that stitches their team right up. Teams aren't prepared to defend, so are caught on the counter, and are in a prolonged state of emergency defending. They are unable to regroup and reorganise, and so have to hope for a foul or a clearance. This leads us to example some preventative measures.

Essentially there are two extremes. All teams, good teams at least, consider their defensive security when attacking. For me, it's leaving three back. If playing with four defenders, I encourage the two full backs to push on and join in with the attack, with one central midfielder holding deep as a shield in front of the two central defenders. Other coaches have different strategies. The traditional English long ball team will play 4-4-2, sit fairly deep, and not leave that structure. The ball will be played direct to the strikers, or even behind the opposition defence. Two banks of four provides ample defensive security, direct passing gets the ball away from your goal and closer to their goal very quickly, the ball is in the air a lot so cannot be contested, and the combative nature of the strategy will mean plenty of set-pieces (also providing dead time). This is defensive security. Plenty of time is wasted, your players are rarely pulled out of position, and they don't give the ball away in their own half. Simple.

Possession teams go about things a bit differently. Their defensive security comes from knowing they have the ability to pass well. They have confidence in their ability to keep the ball in tight areas. They won't give the ball away cheaply, and know that while they have it, the opposition can't score. It's here we see the Barcelona 15 pass move in action. Much like that amazing Rovers goal earlier, they will obviously try and score a goal quicker than that if the opportunity presents itself, but they won't go forcing chances, instead being patient and waiting for the right time to strike. With this fifteen pass move, they are able to move their players around the pitch into more effective positions. Their defensive security comes not only from keeping possession for such a long time, but also this comes with other added benefits. It will keep the opposition camped in their own half, meaning that if they do win it, they will have further to travel to goal. The fifteen pass move, as well as attacking effectiveness, will provide positional defensive security in the form of certain players left in certain positions. And then there is the high press that often comes with possession football. If this team loses the ball, which, although unlikely, will be in the opposition's half, then because they've only been making ten or fifteen yard passes, they'll only have ten or fifteen yards to run when they press, meaning they can win the ball back again quickly after losing it. Amazing.

I like the defensive security of having a defender drop deep, or even a sweeper keeper, being available for recycles. When stuck, turn around and pass to someone that will be completely free and far from pressure. I believe in keeping the ball, but then I would, as I largely work in developmental environments, and believe you can't improve technique without the ball.

Barca pressing to regain possession within six seconds.

That's pretty much this piece done. I maintain as a coach that it is easier to get your defenders to attack better than it is to get your attackers to defend better. Value the transition. Value the off the ball work. Value the eighty nine minutes that you as an individual spend without the ball.

Further reading:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-37327939

http://www.gelfmagazine.com/archives/creating_order_from_soccers_chaos.php

http://www.soccerbythenumbers.com/

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/may/24/numbers-game-everything-football-wrong

http://www.soccerstatistically.com/blog/2013/7/15/goal-time-analysis.html

http://blog.annabet.com/soccer-goal-probabilities-poisson-vs-actual-distribution/

http://www.soccermetrics.net/paper-discussions/goal-scoring-probability-over-the-course-of-a-football-match-2

http://stats.stackexchange.com/questions/168411/probability-of-a-team-scoring-a-goal

https://tacticalpedia.com/training/play-principles/negative-transition-2/

http://spielverlagerung.com/tactical-theory/

No comments:

Post a Comment