Here's a link to the original thread which sparked this article.

Outlined here:

Had player meetings this week. Took it as an opportunity to get to know them, and help them reflect on their performance and look for areas of improvement. Players were 10-13 year old boys. Here are my findings.

Every player said school was more important than soccer. You won't find that being said with a similar frequency in Europe or Latin America. Even the players who ranked soccer as being 10/10 For importance.

A few were honest and said soccer was of medium importance to them. This caused some pearl clutching from parents. It's their life, their choice. Performance is often a reflection of investment and commitment. Explains a lot.

A couple alluded to maybe wanting to go pro, but none displayed a burning desire. This is consistent with the effort and commitment displayed during games and training. No one ever plays or practices as if their life depends on it.

A few had the confidence and felt safe enough to tell their parents to stop shouting, stop pressuring them, and one even flat out said to me in front of his parents that he is forced to play soccer.

Some put winning high on their list of priorities from soccer, which would be inconsistent with their actions. I believe they felt that was a necessary thing to say to impress coach. They never seem upset or angry when they lose or play bad, so do they truly care about winning?

Everyone said soccer is fun, but could not articulate what was fun about it. This caused them to scramble for generic answers like winning and playing with friends.

When asked about their favourite recent soccer moment, all but one said a goal or a win. One boy talked about a very specific pass he played that nearly lead to an assist. This kid will go the furthest.

Most boys ranked themselves as high or average for watching games on TV. When questioned further, turns out very few are even watching one per week. Told them I can often watch three per day. Our standards for "A lot" are far apart.

For pretty much all of them, video games take up a huge amount of their spare time. Video games aren't as bad as the world likes to make out, and have plenty of advantages, but this eats into sunny Saturday afternoons when they should be at the park with their friends.

The amount of kids who do practice in their spare time was devastatingly low. "Sometimes I juggle" was standard, no more than once per week. None meet up with friends to play informally. Some have brothers they play with in the back garden.

A lot of them would enjoy their team better if we didn't have so many ball hogs. They are too old to provide this childish an answer. Believe this is reinforced by parents who don't understand angles and positioning, thinking "he never passes to my son."

Some of the less physically developed kids wanted to be able to kick the ball further. In the US we put them on big pitches too soon. This makes them feel like they have to boot it, because bigger kids dominate. My smaller players are the more skilful, but never feel it.

Upon self reflection, most of them put down physical attributes as things to work on. Need to be faster or fitter. None are remarkably slow or unfit, but they believe these to be the keys to soccer prowess. Parent influence? Big fields too young?

Disappointing that even with the way we teach them, and all we cover, awareness, movement, anticipation, passing, dribbling etc. did not come up more frequently. Would have thought those accusing others of ball hogging would have wanted to improve their dribbling.

Felt like maybe there were a few brown nose comments. I know I am funny, and it also pains me that I am the best coach these kids will ever have. But the meeting isn't about me, so why say these things? It doesn't make you a better player or get you more game time.

During the meetings, upon questioning, some changed their answers. Seemed like the kids were trapped in a web of wanting to tell the truth, trying to fulfil the demands of their parents, and telling coach what they want to hear.

They spoke very differently when they realised they could be honest. So much useful information came out when they removed the filters. It's like they don't realise I can see through their facade. Can't help you if you don't tell me the truth.

What do these observations tell us? I think that much of the purpose of a child in American culture is subservience to the parent, rather than the child being an individual that has agency over their own life. I keep saying that youth sport is entertainment for coaches and parents, more than it is an arena for kids to enjoy themselves.

These reviews felt as much about the parent as it did about the kid. For many, their kid's performance was a reflection on them. If coach thinks my kid plays soccer good, it means I'm a good parent. Not exactly. Short-termism was rife. At the end of these, many kids asked me a question that was prompted by the parent.

"Do you have anything else you want to talk about while you're here?"

The kid stares blankly.

The parent then nudges the kid and says "Go on, ask him." This leads the kid to then ask me "What's one thing I need to work on?"

Not only did this demonstrate that the previous nineteen minutes were a complete waste of everybody's time, but it also showed how, for many, they thought all their soccer problems could be solved by one drill or exercise.

"Oh, that's easy! All you got to do is do fifty push-ups a day! That way, you'll grow to be taller, and you'll be faster, and you'll be able to protect the ball better. Also, the strength in your arms will allow you to boot the ball further, as you can use the extra mass as a counterweight to propel your momentum through the ball. This will solve all your problems, and you'll notice significant improvements within two weeks maximum."

I often think that we offered these reviews as more of a marketing ploy than anything else. We were the only club that did them. I never noticed anything to suggest that they were beneficial, other than convincing parents we were better than other clubs. That's all American youth soccer is, right? We're better than them, so give us your money. We were better than other clubs, but not because of this. After the first few, I then started to use it as twenty minutes to educate the player, and more importantly the parent, as too many of the dads sat front and centre, like it was their own review.

I broke down the principles of play, and went into detail about concepts such as movement, awareness, support angles, and how so much of what you do is really about ball retention. Can you dribble, receive, or pass better, so that you or our team maintain possession? This way, we can get the ball up the field, and are more likely to score goals, while prevent the concession of goals at the other end. This comes from vision, which is affected by positioning (angles) and body shape. What you see determines what choices you can make. If you don't have a decision by the time the ball arrives, it's too late. Some parents even made notes, treating it like a seminar.

Yes, I certainly did go over these concepts in our practices. Three times a week. It was the basis of everything we did. The kids reacted to this like it was new information. And that is why they fail.

Many asked about what drills they could run at home. We both knew that whatever I said wasn't going to happen, because if the kid was really interested in football, they would have already been doing something by themselves. I still took the time to show them some stuff, and physically act it out, as a way to blitz the parent with information, thus showing them I know what I'm talking about and should back off. It really doesn't take a lot of effort to look up these types of drills on YouTube, which any intrinsically motivated kid would have probably done already. Further still, it doesn't take much imagination from an engaged soccer player to go out back and work on receiving from a wall, dribbling round imaginary defenders, or taking shots into a goal (or between trees).

The irony is, if you liked football that much, you would already be going outside and doing the things you like. I like long shots, free kicks, and volleys. With my coaching equipment, I would use poles for a wall, and work on my free kicks. I would throw/dribble/pass the ball in a direction forty yards from goal, then run onto it, and have a shot anywhere between thirty-five and eighteen yards out. I would also use a rebounder to set myself up for volleys. Those are my favourite things to do, and because I like them, and because I like football, I would go out and do it.

The fact of the matter is, these kids don't like football that much. They kind of do. They said as much in their own words. So why do they need all this stuff? Why do we masquerade as if youth sport has to be super serious and professional? Because the parents have no hobbies, and the clubs want your money. You, as the consumer, want to feel important, so we give you loads of unnecessary crap. By giving you unnecessary crap, we can justify charging a fortune. Everybody is happy. Apart from the kid, maybe, but who cares about the kid?

Time to throw more sentiments at you from another Twitter thread.

Next up, why are we so obsessed with skill development, statistics, and how we are getting it all wrong.

Ever had a player come up to you and say "Coach, I can do X amount of juggles!" At what point does it go from achievement to big whoop? When a player can seemingly juggle indefinitely with their feet, is this a useful skill or a circus trick?

Parents have often informed me with such glee. My kid can do this many juggles. Big deal. Still can't trap a ball, beat a defender, or play an accurate pass.

Don't get me wrong, kids in other countries have a personal best juggling record. It's just not front and centre on their resumé. Why? Because aside from the fact it tells you how many juggles you can do, it tells you little else.

Americans love a number; beep test, forty yard dash, bench press, mile, deadlift, shot clock etc. I believe there are two factors at play. The first one is that this is a society based upon dick measuring. We always have to find a way of being better than the other guy.

This takes us down some pretty dark alleys. We should want to be the best we can for our own intrinsic desires, not because of how we are perceived against others. That's petty and short sighted. Pretty limiting.

Ever seen that advert... your brother in law is nice, your sister likes him, mum likes him, dad wants to go fishing... wouldn't you like him a bit more if you made more money than him? No other country would be so brash in their marketing.

"Don't get mad at your brother-in-law. Get E*Trade."

We've just whipped our dicks out onto the table. There's no turning back now. You are less of a man, because someone, who by all accounts is a positive influence in the life of your loved ones, makes more money than you. That is absolutely shameful. This is America.

For instance, I'm more impressed by the kid who gets a bachelor's degree, the first in their family to do so, despite coming from a broken home, than I am with the rich kid from two educated parents getting a PhD.

The second reason why we attach numbers to stuff is because we want to give it a value. Remember that not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted, counts.

A kid can do 100 juggles. We can all point to that tangible number and relate to it. Although it tells us little about their ability as a soccer player. But can they take it on their left thigh, setting it across the body to the right foot, allowing to ping a half volley?

That is hard to count, so we can't draw comparisons, and without a number, rank, or value, people aren't interested. Soccer is a game full of nuance and and subjectivity. There is science to the game, but it is an art.

Anyone with a knowledge of musical theory can understand, interpret, copy, explain Jimi Hendrix. But only Hendrix could create that music. The science explains the art. Like how we all speak English, but none of us are Shakespeare.

I believe I am fairly articulate, so how do I become Shakespeare? Let's break it down into chunks. Here's his ten most used words; The And I To Of A You My In That Would writing, or speaking exclusively those words make me a better speaker? Writing them down or saying aloud.

Of course it wouldn't. Because it is lacking so much context. "Coach, I said "the" one hundred times in a row!" You wouldn't be impressed by that, so why are you so impressed by the kid that can do one hundred one footed juggles in a row?

If a writing competition were who could write the same word the most times, and if soccer were simply a jiggling contest, then it would be impressive. But that's not how writing plays looks like, nor is it how football is played.

I encourage my kids to juggle, but not repetitively with just the feet. I challenge them to move it around different parts of the body, manipulating it with difference surfaces, receiving it from different angles, on the move, turning, then finishing with a shot or a pass.

Receiving off a wall in the air, controlling it, and sending it back without the ball touching the ground is far more beneficial. Even better if done in a corner, so you have 90° and two surfaces to play off in different directions.

Juggling games in groups like HORSE or soccer tennis are far more beneficial. Control and release. There's context, changing variables, never the same picture twice. So much more relative to the game going on.

The need to quantify and measure also comes down to wanting to see a tangible level of improvement. I improved my high score of 30 to 50 means I have improved. I get a boost of confidence, my coach gets praise and credit, and parents feel their fees are justified.

If coach asks me to improve how I receive the ball aerially with my foot, settling it for a shot with the laces, I may feel some improvement, but without a number, it is hard to be sure.

The science and art of football don't often overlap, but when they do, and we can quantify the greatness, we have to hammer it home. Challenged players with scoop passes. I counted how many, and heavily praised the one assist, then talked about the why to consolidate the learning.

It's hard for soccer ignorant parents to get the why, and without numbers, they don't get the nuanced improvements. This is one of our greatest challenges as coaches.

Idiots like me will go against conventional wisdom, and will do our best to educate parents, taking tons of criticism. Others will play to the stereotype, doing exactly what is expected of them, playing the classics. And if you lose? "Well, we didn't hustle enough."

Other generic excuses that cowboy coaches use to retain credibility with coaches; Blame the refs Kids didn't want it enough Luck Too quiet out there Didn't take enough shots No one is brave enough to step up Would rather be playing Xbox Messing around with the ball

Are there other ways this comes out other than juggling? Yes; Cruyff turns Toe taps Tick tocks L turns Etc. All completed perpetually, without an opponent, without having received the ball, without releasing the ball after.

Again, don't get me wrong, these are great to do at young ages to embed the fundamentals, but when they start to show mastery, add in variables, otherwise they are getting good at performing perpetual skills in isolation with no transference to the real game.

Why do coaches do it so much? It is easy to manage Ticks the boxes of "all kids have a ball" and "plenty of repetitions" despite not being of tremendous use It looks organised Kids have a task, so they don't misbehave It's what parents expect to see "Fundamentals"

We play against a lot of teams that have taught their kids tick tocks and L turns. The players try them at the most inappropriate times. It's like they think the move alone is enough to beat the opponent.

Like they expect to perform a step over and the defender just magically disappears. Teams can be characterised by players performing random Maradonas when free from pressure. They have never done any of it with a defender, in a game context. Too much isolation. Doesn't transfer.

"Mom did you see my Maradona?" "OMG I'm so proud of you." Kid did it five yards away from a defender. The pointless spin meant that he lost the picture of what was ahead of him, thus not identifying the passing lane. Visual stimulus is a live feed, and he took his eyes off it.

These types of sessions can be half-arsed and phoned in. Then you criticise the kids for not hustling. If they are hustling but failing, it's because they're not fit enough. Send them off for a lap. Parents will love that you're a disciplinarian, and will orgasm over "tough love"

But it's lazy, and it teaches them nothing. This is why I like our innovative player programme, and why I am regularly scrutinising the way we deliver it. Even regularly ask the kids for feedback.

So you can do 60 L turns in a minute, but can you receive on the half turn with the correct foot, baiting the defender with your first touch, and shift your body appropriately take it round them? Reference Iniesta's first goal in Japan.

Context. Think I'll shut up and fall asleep now.

This video is Iniesta's first goal for Vissel Kobe. I honestly don't think that the average American parent could understand why it was so good. Firstly, he's wide open. There are no defenders around him. Then all he does is take three touches; inside of the right foot, outside of the right food, and inside of the right foot. This would lead many think (and a lot of coaches to lazily prescribe) that Iniesta needs to work on his left foot.

Start this next video of this young boy at two minutes. Many parents would conclude that he is a better dribbler than Iniesta, because the boy uses more touches and does more spins.

By the way, kids like this, never make it. Because they're parents are complete twats. That's the science of it.

American parents want numbers, as it helps them contemplate a game they can't understand, and assigns value to things they can't see. One colleague expressed how he had a system for player reviews. He called it "Subjective Objectives." Each player receives a rank for each listed attribute. From that, he works out who his best players are. After he did it with the team he was working on, the player he thought was second best was third best according to his assigned value. So he did it again until she was second best.

List all the players on your team. I used the twelve most common girls names in the USA. Pretend this is a U11 team playing 9v9. Across the top, write all the attributes you consider to be important. On the right, include a column for their total. For each attribute, assign the player their rank. Because you have twelve players, the player you deem best at shooting is given a 1, and the player you deem worst at shooting is given a 12. 1 for the best player, 12 for the worst player. Then add them up in the total column. The player with the lowest score is your best player (like golf) and the one with the highest score is the worst player.

The range was 42-96, and the average was 65. Here's how the girls appear in order.

1. Mia – 42

2. Evelyn – 51

3. Ava – 54

4. Harper – 55

5. Emily – 58

6. Sophia – 62

7. Emma – 66

Isabella – 66

9. Abigail – 75

Charlotte – 75

11. Olivia – 80

12. Amelia – 96

2. Evelyn – 51

3. Ava – 54

4. Harper – 55

5. Emily – 58

6. Sophia – 62

7. Emma – 66

Isabella – 66

9. Abigail – 75

Charlotte – 75

11. Olivia – 80

12. Amelia – 96

According to the numbers you have given them, Mia is your best player, and Amelia is your worst player.

Let's add some colour to the table, to make it more impressive. Red means the player ranked in the bottom three for an attribute, and the other colours represent gold, silver, and bronze. This helps you easily locate each player in each attribute.

Because assigning children arbitrarily determined values and comparing them is cool, we're going to turn it into a graph, to make comparing these pointless numbers even easier.

This graph allows us to easily compare players to the best player, the worst player, and to the average. Everyone above that line is in danger of being cut come tryouts. Isabella and Emma have a chance, while Amelia should already be looking for another team. Probably best to not give her much game time over the next few months, as the blue line shows she is that bad. It's just not fair to the other kids.

If you really want to impress gullible morons with pointless numbers, you can create cool charts like this, personalised for each player. Remember, like golf, the lower score is good. The four points that stick out would be the four areas Mia needs to work on the most, which are her; shooting, listening, GET THERE! and speed. She's pretty good at strength, footwork, hustle, and COME ON! so working on those isn't a priority.

If you really want to bamboozle the parents, make one of these. Can you even read it? Players are on the left, and are each given a coloured line. The line moves from left to right, aligning with the different attributes on the bottom. If the player's line goes up, it means they are bad at that attribute. If the player's line goes down, it means they are good at that attribute. Make sure to conceal the other names, because parents love to compare kids more than coaches do.

It looks good, and it's easy to understand, but I hope you hate it as much as I do. This colleague even convinced another coach to conduct his player feedback meetings via numbers. Players were told things like "you're the third best defender," and that was pretty much it. Parents talk, and they're always looking for a second opinion, so would ask me and other coaches about what we thought (about a kid we hardly even worked with). This would lead them to reveal what was said in other meetings. "He was told he's the fourth best at passing, and seventh best at dribbling." This would not come with much in the way of specifics, like what makes him so good at passing, or what he can do to work on his dribbling. Just, here's your rank.

It gives the impression of having done work. It takes a lot of thought from the coach to put this kind of thing together. But it does not mean anything. Nothing at all. People don't understand statistics.

What makes that kid the fourth best passer? What type of passing? In what area of the field? From which position to which position? In the air? On the ground? To feet? Into space? Penetrating passes? I was always one of the best at hitting accurate long passes over 50 yards. I could bend a ball into someone's run, or get it to land on their big toe. Whatever was needed. But put three defenders on me, stick me in the middle of the pitch, and ask me to find a ten yard pass to a player away from pressure, and I would struggle. So what grade or rank do I get for passing?

Playing as a right back, I could hit diagonals that would put the left winger through on goal, like Beckham to Giggs. Playing as a CM, I would be out of my depth, trying to connect any passes. What's the difference? It comes down to understanding of space and patterns, the awareness, the vision, and the technique required to perform. Being told I am X good at passing doesn't help me become a better player any more than knowing what colour underpants I am wearing helps the reader to become a better reader (enjoy the image for as long as you need to). It's pointless information that helps no one, but it sounds important. And sounding important is all we need when we want parents' money.

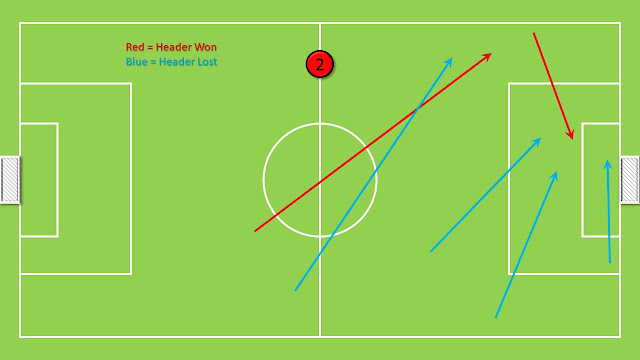

Here's my back four and their heights.

RB (2): 5'9"

CB (4): 6'3"

CB (5): 6'2"

LB (3): 5'7"

So which one is better at heading? Who is worse? You're inclined to say 4 is the best, and 3 is the worst, but you don't want to say that, because you have guessed from the tone of this article that you are probably wrong. You're not wrong, as we don't yet have enough stats to really know.

Here's more info. This is their vertical reach (stationary jump on the spot).

RB (2): 24 inches

CB (4): 13 inches

CB (5): 20 inches

LB (3): 16 inches

By now you've realised that maybe height isn't as important as how high one can jump. Is that what I'm getting at? Maybe. It's certainly another factor. So now you assume that 5 is the best header of the ball, because they are only an inch shorter than 4 in height, but can jump 7 inches higher. You will also note that 2 may be 6 inches shorter than 4, but can jump 11 inches higher. So does that mean that 2 is also a better header of the ball than 4?

No. You know that it's about much more than just that. You know that vision, awareness, timing etc. come into it. As well as strength. Doesn't matter how high you can jump if the other player can muscle you off the ball. So let's assign stats from the game. That will tell you, for sure, which defender is the best header of the ball.

Headers won in the game:

RB (2): 2

CB (4): 7

CB (5): 5

LB (3): 0

Well that settles it! 3 didn't win a single header, so they are obviously the worst, and 4 won the most headers, so they are obviously the best. No. You know that how many headers from how many headers they faced is what's important. Here are those stats for you.

Headers won in the game from number of headers attempted.

RB (2): 2/6 33%

CB (4): 7/10 70%

CB (5): 5/6 83%

LB (3): 0/1 0%

Now we know that 5 is the best header of the ball, because 5 has an 84% success rate. Isn't that how it works? No. Each stat is missing context. What's the context of each header? We can't get those stats at youth level. But let's say we can. Here's some maps to enjoy.

Now can you tell me who is the best at headers? No. You still want to know more. You want to know;

Were they running or stationary?

Were they jumping high? Staying at their height? Stooping?

What was their start position in relation to the location of the aerial duel?

How many opponents were in the vicinity?

How much physical contact was made between players during the aerial duel?

Were they moving towards the ball or were they back peddling?

What was the delivery like? Floated? Driven? Whipped? Spinning? Looping?

Was the delivery from a teammate or the opposition?

And most importantly, where did the ball go after they headed it? Was it possession retained or possession lost? Were the headers passes, clearances, shots, blocks, attempts at control?

We can maybe infer some things from these maps, but not too much, as this was just one game. Like 2 isn't good at winning diagonal crosses into our penalty area. 5 is effective at winning headers from crossing positions wide of our penalty area. 4 seems to have shown competence at winning headers from opposition keeper delivery, attacking corners, and defending from crosses around our box. The information is now a little richer, but still only hints at things. And if you're going to rank players (which I don't think you should be doing with kids) you're going to need some substantial evidence to back up what you say, or else you're just talking out your arse.

I'm not done beating these analogies. In a room of ten people, you are the third richest. First place has £10,000,000, second place has £9,000,000, and you, in third place have £10. You have small change compared to these millionaires, but you're still in third place. So how useful is it to know you're in third place? One year in La Liga, third placed Valencia were closer to the relegation zone than they were to Barcelona and Real Madrid in first and second place.

Valencia in 3rd, with 61 points, were closer to relegated Villarreal in 18th with 41 points (20 point difference) than they were to Barcelona one position above them in 2nd with 91 points (30 point difference). So being told your kid is the third best shooter on the team, what does it actually tell you? Without context, it tells you nothing at all.

Let us go back to our imaginary U11 girls. This is how you ranked them for shooting.

|

Name

|

Shooting

|

|

Emma

|

12

|

|

Olivia

|

11

|

|

Ava

|

10

|

|

Isabella

|

4

|

|

Sophia

|

5

|

|

Charlotte

|

8

|

|

Mia

|

6

|

|

Amelia

|

9

|

|

Harper

|

2

|

|

Evelyn

|

3

|

|

Abigail

|

7

|

|

Emily

|

1

|

You have stated in your subjective assessment that Emily is the best shooter By assigning equal value to each rung on the ladder, if you will, if placed in order, one would assume their shooting ability may look something like this.

|

Name

|

Shooting

|

|

Emma

|

12

|

|

Olivia

|

11

|

|

Ava

|

10

|

|

Amelia

|

9

|

|

Charlotte

|

8

|

|

Abigail

|

7

|

|

Mia

|

6

|

|

Sophia

|

5

|

|

Isabella

|

4

|

|

Evelyn

|

3

|

|

Harper

|

2

|

|

Emily

|

1

|

Remember that in this graph, the player with the lowest score is the one determined to be the best.

This is how it looks. And you've probably determined Emily is the best shooter because she gets the most goals, because you're a dumbass, and not taken into account; delivery, shot position, goals to shots ratio, keeper positioning, striking techniques, movement to receive, deception, effect used on the ball, location of defenders, first touch etc. Is Emily really one step better than Harper? And is the difference in ability between Emily and Emma how this graph plays out?

It just so happens that there is a loose correlation between shooting ability and goals scored. So now, I will assign goals to these girls. I will also flip the values, so that the best player receives a 12 and the worst player a 1, allowing us to better compare data.

|

Name

|

Shooting

|

Goals

|

|

Emma

|

1

|

1

|

|

Olivia

|

2

|

1

|

|

Ava

|

3

|

2

|

|

Amelia

|

4

|

5

|

|

Charlotte

|

5

|

8

|

|

Abigail

|

6

|

12

|

|

Mia

|

7

|

13

|

|

Sophia

|

8

|

17

|

|

Isabella

|

9

|

22

|

|

Evelyn

|

10

|

30

|

|

Harper

|

11

|

32

|

|

Emily

|

12

|

45

|

U11 games are high scoring, and you have been collecting data for a couple years, including every tournament, indoor, futsal, and league game. Here's the graph.

The blue line is how you ranked the players for shooting ability. The orange line is goals scored by that player. You have decided you feel shooting ability is directly proportional to goals scored (in reality, it's one of many, many factors). Harper, who is second best, by the blue line, is only a little bit behind Emily, only one place. By the orange line, Harper in second, is very far behind Emily in first. If there were actually a way to determine a player's ability, this would be a much more effective way of showing is than subjectively assigning each player a rank.

Messi is the best player at Barcelona. If he were to join Aldershot Town, he would also be the best player there. The second best player at Barcelona is much closer to Messi than the second best player at Aldershot. The thirtieth best player at Barcelona is much closer to Messi than the second best player at Aldershot. Ranking them does nothing, other than make you look what you know what you're talking about in front of parents.

These are the ten best players on FIFA 20. Their rankings overlap. It's not very scientific, but even this is a far more scientific method for differentiating between player attributes.

Do you ever assign players a performance score after a match on a review sheet? Just for informal reference.

Here's an imaginary run of six games.

|

Name

|

Game 1

|

Game 2

|

Game 3

|

Game 4

|

Game 5

|

Game 6

|

Average

|

|

Emma

|

7

|

6

|

6

|

7

|

5

|

4

|

5.8

|

|

Olivia

|

8

|

4

|

8

|

7

|

4

|

7

|

6.3

|

|

Ava

|

8

|

4

|

8

|

6

|

5

|

8

|

6.5

|

|

Amelia

|

9

|

5

|

9

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

6.8

|

|

Charlotte

|

7

|

3

|

10

|

8

|

5

|

9

|

7.0

|

|

Abigail

|

9

|

4

|

6

|

7

|

4

|

9

|

6.5

|

|

Mia

|

7

|

5

|

7

|

8

|

7

|

7

|

6.8

|

|

Sophia

|

9

|

4

|

8

|

6

|

3

|

6

|

6.0

|

|

Isabella

|

8

|

5

|

8

|

8

|

8

|

7

|

7.3

|

|

Evelyn

|

9

|

6

|

8

|

5

|

3

|

6

|

6.2

|

|

Harper

|

8

|

4

|

7

|

6

|

6

|

8

|

6.5

|

|

Emily

|

9

|

4

|

9

|

7

|

5

|

9

|

7.2

|

|

TEAM

|

8.2

|

4.5

|

7.8

|

6.6

|

5.1

|

7.25

|

6.6

|

Each player receives a rating out of ten for each game. At the bottom, is the team's rating for that match, which is the average of all the player ratings. The right column 'Average' is the average rating for that player over the six games.

Why are there peaks and troughs? Sometimes the team played well, other times it didn't And what affects that? So many things, it's pointless even to discuss it. Some players are more consistent than others, whereas some bounce around from performance to performance. You have a squad of twelve individuals. Why did Charlotte get a 3 in Game 2, when the team average was 4.5? And what happened the next week when she was the only player to receive a 10 rating in that six game stretch? It could have been anything. Maybe she had a bad day at school or home, or a bad week. Maybe she had played volleyball that morning, and been to a sleepover the night before. Or maybe the player marking her was fantastic that day, and Charlotte couldn't do anything about it.

If you're just basing this stuff purely on the eye test, it doesn't help anyone. And to parents, if you spend twenty minutes listening to coach talk in a meeting, with criticism and feedback, and yet cannot answer how to improve any of the attributes, it was a waste of time full of waffle and hot air.

"Your kid needs to do X better because they are ranked 11th on the team at that." Okay, but how? Without a plan, pointing out deficiencies is akin to asking someone to be taller.

Does the coach talk the whole time? Bad. Coach needs to get to know the player. That means listening to the player.

Do you the parent do the talking for your kid? Bad. Shut up. They won't become confident, brave, and independent if you rob them of opportunities to become so.

This is how I did it. The sheet on the left is the player telling me about themselves. What they like, why they play, and asking questions that dive into their motivation. That means I get to know them better. Below that, as you can see on the right (it's the same sheet) is some questions for them to fill out. They can tell me through here how much time they dedicate to football, and how much they care about it. The sheet in the middle, the spiral, is a performance wheel.

For the performance wheel, players have to first determine what is important for the position they play (or want to play), so that we don't end up telling our goalkeeper they need to improve their shooting. They then state how good they are at each of these attributes, assigning themselves a number out of ten. A simple performance looks for the weakest attributes in the most important areas. And then we focus on improving those two or three issues.

Self-reflection is important. As I keep saying, everyone's favourite subject is themselves. And you must look at each player as if they have "make me feel important" written on their forehead. Talking at them for twenty minutes will not do that. You won't establish a connection with them, and you won't learn anything about them.

Some of my very favourite human beings were more than happy to write these messages on each other's faces for the purpose of the club curriculum booklet I made.

"Include me."

"Challenge me."

"Engage me."

"Inspire me."

"Make me feel important."

That's how you're supposed to look at players. Like these are subtitles permanently hovering above their faces.

At Aldershot, our reviews were rather different. I'm guessing not many in the US are done like this. For one thing, we conducted the reviews in the posh rooms inside the stadium, because, you know, real countries have youth teams that feed into a professional club rather than being a money making scheme to scam parents. We had to wear suits, as the coaches, and the players had to have a smart bottom half, and the club hoodie on top. I think they got twenty minutes or half an hour with each of us.

They had to present to us, what they thought were their strengths and weaknesses, back it up with reasoning, and then talk about what they were going to do better. The presentation method was up to them. PowerPoint, notes, cards, pictures, simply speaking. We had our laptops and tactics boards there if they needed them. This put the kid in charge, and let them communicate via their most preferred means. We're not forcing them to adhere to arbitrary presentation standards, but letting them speak naturally.

I would say that unless the kid has realistic ambitions of going pro, there's no real point having one of these meetings. So you impress the coach? Who cares. I had much more respect for the lazy kids of Missouri who didn't book a meeting, than the half-arsed kids who attended a meeting to blow smoke up my arse. The kids who stayed home were at least being honest.

While the Aldershot boys presented about their abilities, ambitions, and plans, we might interject only to answer a question, or probe for further detail. It was player lead. You drive yourself to your destiny. As coach, I can only give you directions. As these kids wanted to be pro, there were improvements made within the areas outlined. The kids in Missouri, very little happened as a result of those meetings.

As mentioned, I took the time to educate parents. "You don't need to do five hundred juggles. Only two; one to settle it, and one to release it."

"So you say you're bad at passing. Why?" And it would always revert back to positioning, body shape, angles, first touch, and vision. The reason you can't make a pass is because you can't see your next move. 90% of the meetings we would spend about five minutes on our feet, working on receiving angles, open body shape, how to gather information, and how to decipher it. That's where the pass goes wrong. Not a lack of concentration or hustle.

In conclusion, next time you do a player review, who is it really for? For you, the coach, to feel good about yourself? To appease the parent so their feelings and impressions towards the club grow? Or for the kid, providing them with useful information and guidance to become the player they want to be?

No comments:

Post a Comment