I started working at my primary school in September of 2020, at a time when we were still under some restrictions, but not many. I would have 25-30 kids for just under two hours (about 90 minutes of actual PE time), and I would see them every two weeks. We were not allowed to do contact sport, which meant so many directly opposed activities went out the window. I found much of the learning to be repetitive, boring, isolated drills, with little to no purpose. More of an arbitrary box ticking exercise than anything to inspire the athlete within kids.

During this early 2021 lockdown, things are different. Now, less than half the kids are coming into school, due to the government restrictions. In most cases, these kids are the children of key workers, and I will have around fifteen of them. It can vary, with some kids being different, but typically I am working with a group of 10-15 kids, and 90% of them are in school consistently. On top of that, I'm seeing them weekly now.

To illustrate that point, here's how it would typically go:

Week 1

Mon - Year 2 A - 25-30 kids

Tue - Year 4 A - 25-30 kids

Wed - Year 6 A - 25-30 kids

Thu - Year 3 A - 25-30 kids

Fri - Year 5 A - 25-30 kids

Week 2

Mon - Year 2 B - 25-30 kids

Tue - Year 4 B - 25-30 kids

Wed - Year 6 B - 25-30 kids

Thu - Year 3 B - 25-30 kids

Fri - Year 5 B - 25-30 kids

In one week, I would work with 125-150 kids, and then the next week I would work with a different 125-150 kids, rotating each week.

There are several problems with this;

I cannot remember their names.

Building any relationships with them has been extremely difficult because I can't remember their name, and there's no consistency because of how frequently I see them.

Their progress is minimal if there is any at all.

The large numbers mean that most kids fly under the radar during the lesson, and are given very little individual attention at all.

One poorly behaved child can ruin it for the entire group because their troublemaking affects 25-30 kids.

The range of abilities in such a large group is incredibly broad, making it hard to know where to pitch a session for maximal or optimal engagement. It's always too easy or too difficult, too fast or too slow for somebody.

The range of motivations in such a large group is incredibly broad, again, making it hard to know where to pitch a session. Are they beginners or keen athletes? Do they love sport or hate sport? There's a kid in a professional academy in the same class as nosepickers and butterfly chasers that are allergic to being outside.

The coronavirus restrictions have made it even harder to plan and adapt. We talk about having a coaching tool bag, where the coach brings out different tools depending upon the situation, to deal with whatever is in front of them. With the restrictions, over half of my tools have been taken from me, and many of them were the most effective tools.

To try and summarise; I don't see them enough to get to know them, they don't do enough physical activity to actually make any progress, the range of abilities and motivations makes it very difficult to pitch and plan a session, and the coronavirus restrictions give me less tools to work with.

Yet now, in this lockdown where only the key worker kids are coming in, things are different;

I see the kids frequently enough that I have now got to know them, and they know me. I actually know most of their names now.

Better still, I am getting to know their personalities, so can communicate and adapt my teaching in different ways to suit the individual.

With the vastly reduced numbers per lesson, they all get more of my individual attention. I can help those who are struggling, and I can challenge those who find it too easy, rather than neglecting or ignoring them.

And it's harsh to say this, but most of the troublemaker kids aren't coming into school. Most of the kids coming in now have to come to school because their parents have jobs, which I think really makes a difference. There's less outbursts, tantrums, arguments, disobedience. The main culprits haven't been into school recently, because their parents aren't key workers.

I have, however, had one tool taken away from my tool bag. On top of the restrictions that were already in place, we now cannot do any passing between students with their hands. Before, we could practice throwing and catching with others, and now we cannot do that. On the surface, this makes things more individualised, but we can still do work in groups or teams.

My preferred method for teaching is TGfU, but I do use others from time to time. Even when we have to be socially distanced, unopposed etc. there are still ways we can apply a constraints-led approach.

If everything is an interaction between the learner, the environment, and the task, what's changed the most is the environment. We're doing many of the same exercises, although the lower numbers allows me to do other activities due to having less kids to manage, and having reclaimed much of the space. There's less noise, less interference, less waiting for the troublemakers to behave, less waiting to get in line, less waiting to get a ball each, less waiting while I repeat myself for the fifth time because the same handful of troublemakers weren't listening yet again. Most kids aren't bad, but most kids are susceptible to silliness through loss of attention. That comes when we're waiting, when the kids are being idle. We've got less than half the number of kids now, but probably less than a quarter of the previous time spent being idle. Another factor is that now I have a relationship with the kids, and I know their names, my discipline is more effective with them. I feel like many before looked at me with substitute teacher syndrome. Now it feels like I'm actually a member of staff.

What's funny to me is that the kids actually cheer when I come in. When I walk through the playground to setup while they are in their recess, they will swarm over to me, ask me questions, and even though they know it's their turn to do PE, will still have to clarify several times. They become so excited to be active, and it's great. I'll talk more about that later.

Using the STEP principle, let's look at what has changed.

SPACE - We're using the same spaces, either in the hall or on the playground, but relative to the number of kids, the space has increased. There's now fifteen kids in that area, rather than thirty.

TASK - We're doing many of the same activities and exercises as before, but also due to the reduced numbers, I've been able to add some more in.

EQUIPMENT - We're using the exact same cones and balls as always, but additionally, two basketball hoops too. Before, two hoops was not a good enough hoop to child ratio, so we never used them due to the long lines that would form when waiting for turns.

PEOPLE - This factor, with the space, I believe is the biggest difference. Not only are there less kids, but the percentage of trouble makers within the group has vastly decreased. In a group of thirty, there would be five trouble makers. In a group of fifteen key worker children, there might only be one trouble maker, with the other four staying home. The balance has been shifted massively.

The above coach to player ratios were taken from US college sports. For most of the school year I have been around 1:28, but now I am typically around 1:15. Massive improvement. My best sessions have been when there is a teaching assistant around, as it gives another set of eyes, another pair of hands, and another voice. They can deal with the injuries, the tears, and tend to the tantrums, leaving me to do my job of actually teaching some sport.

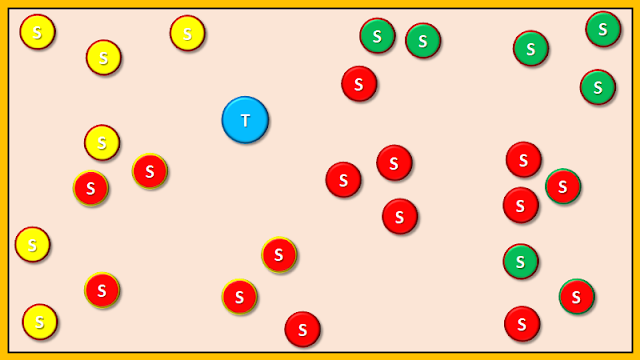

This is an aerial view of me (T) working with 27 students (S). Look at the space that is covered.

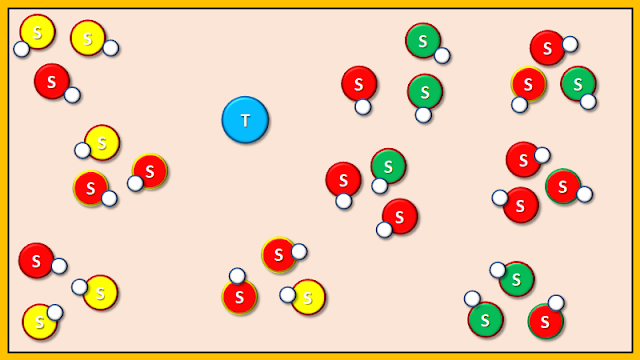

Here I am working with only twelve students. We're using the same space, but but now it feels like everyone can spread out more. They can work in groups or as individuals with less bumping into each other, and less getting in the way. A kid drops a ball, it goes to where someone else is working, who kicks it away, and an argument breaks out. That's less likely to happen here, as each individual only has eleven potential classmates to interact with, rather than twenty six, and the area in which everyone occupies has increased. You can also see now how there are less kids for me to monitor, so that everybody receives some observation time, affirmation, correction, and guidance.

In any group, the members can be split into one of three categories; positive influencer (green), negative influencer (yellow), and neutral (red). The positive influencers are those really great kids. The dream children who make you think having kids isn't so bad. They are polite, attentive, thoughtful, considerate, funny, helpful. Then there are the negative influencers. These kids are the most effective contraceptive I have ever seen, as they put you right off having kids. They are loud, angry, stupid, short on attention, disrespectful, selfish. Their behaviours are destructive to the group, due to not listening, not paying attention, cheating, deliberately winding others up. So many great examples to think of. In the middle are the neutrals. These are just your average kids, who can be easily swayed. Depending upon the strength of the group, they will become, or at least empower, either the positive or negative group. It's like a tug of war, with the positive influencers trying to drag the neutrals up to their level. and the negative influencers trying to drag the neutrals down to their level. Think of the angel and the devil on your shoulder. The neutral kids will observe and see which behaviours go unpunished or rewarded, and will be swayed one way or the other.

We must also factor in the teacher. The teacher has their own methods of different levels of effectiveness, which can depend on the relationship with the students, and with the number of the students. Some neutral kids can be primed by the teacher, and some of the negative influencers can be converted (on a temporary leading to a permanent basis). It requires constant nudging, reminders, and reinforcement. Remember that kids are not attention seeking, but connection seeking. I believe the negative influencers to be twice as strong as the positive influencers, so in the group above, the pull of six negative influencers will be stronger than the pull of the six positive influencers. At even numbers, the lesson is already in the negative. It's up to the teacher to bring it back to positive, which is very hard to do.

If we add a second teacher, it becomes easier to manage, as each individual receives more attention, and spends more time being monitored under observation. With one leading and one following, one teacher can direct the lesson, while the other tidies up by dealing with the distractions.

As time elapses, the neutral kids start to convert (see the ring around some of the neutral kids has changed colour to indicate they are converting). Again, this will depend a lot on the strength of the teacher(s).

With the kids now spread out around the playing area, working in their groups of three we can see how the influence might start to filter across the playground. A neutral kid might not be converted one way or the other. When working with negative influencers, the neutral kid won't call them out on their poor behaviour. Likewise, when working with a positive influencer, the neutral kid might be resistant to the good behaviour too.

Some do suggest mixing up the groups as illustrated above, to get different dynamics working. But in my experience, it doesn't work in this setting. Remember that most of these kids didn't choose to be doing physical activity. They do not share the same motivations. Unlike a team looking to improve, interact socially, and win at the weekend, in this PE lesson, we will have kids that love sport, some that hate it, some that are enduring it, some that enjoy PE but not the activity we're doing this week, some won't participate unless they are with their best friend, and some are just in a bad mood today. The pull of the negative influencer becomes stronger because they are exposed to more neutrals, and are able to infect more students. In the picture above, there are a few examples of there being a green, red, and yellow together. In most cases, the yellow (negative influencer) will win the battle and convert that red (neutral) into another negative. It's the proximity that causes it to spread through the group. It's not a popular take, I'm sure, but if my goal is to maximise participation, then I need to keep the negative influencers away from the rest. I could have six negative influencers working in isolation, dossing around, and that would leave me with twenty one other kids that are actually taking part. Or, I let the negative influencers infiltrate the group, and take more down with them, and now I only have around ten kids participating.

Is this a defeatist attitude? Are the better ways of dealing with it? Certainly. Give me half the kids and an assistant, and I'll deal with it better. The good kids don't deserve to be neglected because a handful don't know how to behave. It's not my job to course correct their behaviour, especially not only during a ninety minute session every other week. And if the parents are upset, teach your kid how to behave, then I can reach them.

Now with only twelve kids, and most of the trouble makers staying home, look at how that affects the group dynamics when they work in threes. We can have way more of a positive impact, and start to see the benefits of peer-to-peer learning, which is something I do all the time when coaching football, but haven't been able to use at school until recently.

Even better when it looks like this. The neutral kids are more likely to be kept on task. The negative influencer has less peers to infect. There's more space between the negative influencers and the other students. With two teachers, the circuit can be broken.

In this example, every kid has a ball. Can you see how they're going to bump into each other a lot? And can you see how hard it is for the teacher to monitor all of them?

In the absence of team sports, many schools in the area have signed up to virtual games. This is where we test the kids at school, and submit the best results online. One such test is to bounce the ball as many times as you can in a minute. Count each bounce, and then, if you make a mistake, start from zero again. Whatever your highest score is what you tell the teacher. I'm hoping you have identified many things wrong with this already.

Despite what I was told by my strict child hating private school teachers, teachers do not have eyes in the back of their head. In the above picture, the blue triangle represents what the teacher can see. I reckon that's fourteen kids within the teacher's vision. Can you watch fourteen kids at the same time? What about the thirteen you can't see? Who is ensuring they do it correctly?

I'll walk you through the process here.

Every kid lines up, and you tell them to get a ball each. They have to do it in a line because they crowd the bag and fight over the balls. Sometimes I do this with the positive influencer kids as helpers to hold the bags open.

It takes a good minute or two to line up, because a handful of negative influencers haven't yet finished their conversation. While waiting, two more negative influencers who were in line, decide they want to run around the playground instead. They've tried being still and silent for ten seconds, and decided that it wasn't for them.

Eventually the kids are in a straight enough and quiet enough line to now retrieve the balls. You remind them again, for what feels like the hundredth time that lesson alone, to get their ball and stand still. Do not throw, bounce, or kick, as this makes noise, and distracts the others.

One by one, the kids get their balls, and then find a space to wait for instruction. Inevitably, one of the colours is exceptionally popular that day, and a kid who wanted a yellow ball finds that there are no yellows left. This causes tears. The line is now held up, while you tell this kid to pick another colour. "I want yellow" they reaffirm. You try telling them that the colour is not a big deal, and just to get on with it. This results in a huff, and walking away in a strop, with the kid refusing to take part unless they get the colour they want. While you now tend to the tantrum, some of the negative influencers who already have their balls have helpfully forgotten your instructions to not bounce, kick, or throw the balls.

Like dominoes, many of the neutral kids also start to play with their balls. Why? They are idle, and they have seen the others get away with it. They have a colourful, bouncy ball in their hand, and they want to interact with it. The teacher is distracted, and the other kids are doing it, so they make a choice, believing they probably won't get in trouble for it.

The child having the tantrum has now decided they'll use a green ball, because their friend also has a green ball, and ninety minutes of PE with the wrong colour ball is better than going inside and reading alone. You start to reel the kids back in again, thinking it's all under control, and one of the neutral kids drops their ball near a negative influencer. The negative influencer decides it would be hilarious to boot that ball as far away as possible, and the laugh in the face of the neutral kid. The neutral kid starts to cry and comes up to you, tugging your jacket (proximity in a pandemic) to tell you what you already saw, and are already responding to. The negative influencer kid denies they did what you saw them do just five seconds earlier, and then begins their own tantrum about how unfair life is, before you can even punish them. This leads to them throwing their own ball away in a huff, ignoring your commands to "come back here!" and then sitting on the bench, arms folded, after knocking some other kid's drinks bottles on the floor.

While you deal with the negative influencer, who also denies hitting the bottles, chaos starts to break out with the rest of the group, now playing some sort of game with their balls. You warn the negative influencer having a huff that another outburst like that will have them removed from the lesson. Again, they protest their innocence, and proclaim the unjustness of life.

Now you have got the whole bunch in, apart from the kid in a timeout. You start to explain the exercise. It's a very simple exercise, that requires no more than a fifteen second explanation, and a ten second demonstration. To some kids, it feels like the reading of War and Peace. This leads to conversations breaking out, and some kids beginning to bounce their balls, which competes with your explanation for airtime. You reprimand the kids that were making the noise, and you try again. You explain as simply and as basically as possible.

"You have one minute to bounce the ball as many times as you can. How long do you have?"

Class responds: one minute!

"For the first go, you're only going to use your right hand. Which hand?

Class responds: right hand!

"Good. Like this..." You start to bounce and count... one... two... three... four then you deliberately make a mistake.

"Oh look, I dropped it!" This prompts three kids to fight over retrieving the ball for you. The irony, which is lost on them, is that their rapid response, multiplied by three of them getting in each other's way, meant that it took longer for you to get the ball back.

"Thank you. I've made a mistake. So I start again from zero... one... two... three... oh no! Another mistake! What was my highest score?

Some kids will shout out the right answer [four], some will shout seven, and many will look at you like you've been speaking Chinese.

"Get it? See how many you can do in a minute, then when I tell you to stop, you tell me what your highest score is. I need your name and your number, as I write these down. For example, I'm Dave and I scored ten. Like that, please."

You look at your watch to start the timer, and realise it has been fifteen minutes already, and you have achieved nothing with the group. You blow the whistle to start the timer. A handful of kids are stood there motionless, not realising that it is time to start. Most catch on within ten seconds. Then there's always a handful which don't. They turn to you with that confused look on their face, some with a look of offence, as if to say "how dare you spring something so complex upon us!" and ask "What are we doing?"

That question is always asked in a slow and dopey voice. It's never accompanied with an apology for not listening or asking for clarification when they had the chance. It's never followed by a please or a thank you.

One minute goes by. It's time up. You blow the whistle and call them all in, while you stand there with your clipboard and pen. It takes two minutes to get everyone to shut up. That now makes one minute of activity, and seventeen minutes of standing around talking. "Remember, the quicker you come in to me, and the quicker you become silent, the quicker this goes. Then we can get from the boring stuff to the fun stuff. They unanimously agree that they want to get to the fun stuff. Very few take the necessary actions required to get to the fun stuff.

It's time to get their names and their scores. You wish you knew all their names, but as you see close to three hundred kids on a bi-weekly basis, they're not sticking in your mind. One last gentle reminder. "Remember, give me your name and your score. For example, I'm Dave and I scored ten." Most get the point, but a discussion breaks out as several students realise there isn't a Dave in the class. The kid you witnessed eat a live worm at breaktime puts his hand up. The worm-eater looks at you with confusion and points out that they don't have a Dave in the class. An echo forms, as other children feel the need to point out the absence of a Dave. One kid then loudly exclaims "I'm Dave!" which causes much amusement to the group. British comedy at its finest. Several of the kids, usually girls, then feel the need to point out why it's funny. "It's funny because his name's not actually Dave. He's pretending." I get the feeling they say this to me to prompt me to laugh too, much like when you explain the joke to someone who didn't get it.

We've wasted another three minutes. Kids start to randomly shout out their scores. You tell them that they need to be in a line, and you will go through them one by one. Things actually look orderly for a change. Perhaps we've turned a corner after a bumpy start. Out of the corner of your eye, you catch the kid who was previously in time out, is now on his feet smashing balls around. You tell him to sit back down, and he protests that he is bored, fully missing the point of a timeout. You remind him that if he wants to play, he has to demonstrate that he can behave. Again, with the persecution of the entire world upon him, he sits back down, victim card in hand.

Now we can start to write down their scores.

"Jessica, twenty-four."

"Ethan, sixty."

So good so far.

"Thirty seven."

"Name?"

"Thirty seven."

You stare blankly at the kid, hoping they'll pick up on their mistake. Instead the child looks at you with frustration, taking on the form of an English holidaymaker in Spain trying to order a full English breakfast from the waiter. The kid says it louder. "Thirty seven!"

"I need your name, please."

"What?"

Red rag to a bull. I've been conditioned to perceive this as the height of rudeness.

"Tell me your name."

"Uh..."

There's always a pause. Why is there always a pause when such a question is asked?

You get the name and start making your way through the group. Chatter emerges from the kids who have had their score recorded. You take a moment to remind them they need to be quiet so we can get it over and done with and get to the fun stuff. It says a lot about a lesson when the kids can pick up that even the teacher thinks the idea is stupid.

The kids have now been stood in line, giving their names, for longer than they were doing the exercise. It is vital that we report to the school games partnership how many bounces each kid can perform with their right hand, so although it comes at a great cost of twenty minutes of being idle, it was worth it to extract this important information from such reliable sources. Some trends start to emerge. As always happens following these tests...

Many kids start with "uh..." when giving their number. Their eyes flutter about searching for that place in the sky where they jotted their score down. What follows is something unrealistic and unachievable. You've done these tests, sadly, multiple times before. You know what the average score is, what an achievable high score is, and what is an outright lie. For instance, if the task is to run around cones over a 10m distance as many times as possible in sixty seconds, you know there is a finite amount a human can achieve. Apparently, we've had world record potential children in our school for weeks now, and not noticed it. They set new limits on what is possible. When the average score is coming in between twenty and forty, and the one kid who looks three years older than the rest and who plays at a good level of sport in his spare time gets sixty, there's always one kid who claims to get three hundred. This is not hubris. I have had kids give scores of hundreds and even thousands when you're not likely to get more than fifty even as an adult.

I pause. I look at them. I get them to repeat their score. They stop and think, then decide to commit to the lie. I saw it slower, like I can't hear it properly... "three hundred... and thirty... seven?"

"Er.... yeah."

"Are you sure?"

"Yeah."

"Okay. Just to remind the group that I don't think we have any liars in this class. I'm going to write down what you tell me, because I believe you. You scores will then be published on a website, and the best students from this school will be selected to represent our school against other schools in the county."

While that kid visibly tenses up, a few of the others with genuine high scores become enthused.

"Just imagine for a second, that you lied about your score, and I submit it. You will be invited to a competition to compete against kids that are really good, and who didn't lie about their score. And you will be doing so representing our school. How bad do you think our head teacher will feel if he finds out we submitted a liar to represent us? Worse still, you would have taken that opportunity away from another student, one of your classmates, who deserved to be there. But I trust you, so I will write down whatever you tell me."

I then move on through the group. A lot of round numbers coming in, like forty or fifty. Then we get the jealous liars who add one on to what their friend said.

"Forty eight, Evie."

"Forty nine, Kayley."

"Oh wow! You just beat me by one!"

The innocence of a child. The child who got beat is genuinely unaware that their friend is lying, and at the same time is genuinely happy for their (false) achievement. Sometimes, this reaction causes the liar a little bit of upset to appear on their face, as their lie was accepted by someone who is their friend, without questioning it, accompanied by a congratulatory response.

A few seconds later, the kid to have scored over three hundred comes and tugs on your jacket (again, we're in a pandemic. Stay away). "Excuse me, but I just remembered that I actually got seventy." They have recognised that their lie scored a pants on fire rating, and have decided to dial it down a bit to something more believable. I usually write a zero for their score at this point.

Over twenty five minutes into the lesson, and we've done one, pointless, boring, mundane activity. In the opposed v unopposed debate on Twitter, those who I perceive to be as unimaginative coaches look to defend their frequent use of unopposed drills by saying that all practices are effective. Yes, to some degree. It's just that some are way more effective than others. It's like trying to get to Mars by going 50mph or actually using a spaceship and going thousands of miles per hour. I forget which podcast or audiobook I was listening to recently, perhaps it was Doug Lemov, who talked about minute to learning ratio. One minute of decontextualised ball bouncing has taught the kids as much about basketball as watching a golden retriever in a basketball vest chase its own tail.

I don't know what irks me more; the fact that we are wasting so much time by having kids being idle, or the fact that a lot of the time spent "working" is doing pointless exercises that achieve nothing. Nevertheless, this provides some insight into what I face in one of these "virtual challenge" lessons.

In the more strict lockdown, with less kids, more restrictions, I have been forced to be a bit creative. We're now able to go way off topic, as most of the curriculum now cannot be used. I'll outline a few of the exercises I use most frequently. I'll also note that I'm able to do other things too like peer-to-peer learning. I set the kids a task, ball each, individual work. Something like bouncing, kicking, dribbling, throwing/catching. I'm then able to give them a couple different variants too; an easier way, and a harder way. Kids can now self-organise. Those who find it easier will go for the harder challenge. Those who are struggling will take the easy challenge. It becomes self-governing, and the kids are now trying their hand at something more appropriate to their skill level, rather than using the one size fits all approach.

All sessions should incorporate all four corners. And we should always make time for social and psychological, even starting with that as our way in. Due to the improved coach:player ratio, I can monitor the kids better, and interact with them on a more meaningful level. This is where peer-to-peer learning comes in.

"Hands up who is doing this really well? Excellent. I'd like you four to spread out, and then take a seat on the floor. Good. Now, those who need a bit of help, go stand next to one of those four, and they will teach you like I do."

This has become really effective. The kids who can do it well love to show it to others. Sometimes, their teaching is more effective than mine, because the are on the same level as their peers in terms of communication and understanding, and recently overcame the same barriers their friends are facing. The kids who need help like it, because they are getting the attention they require, and due to the choice, they are working with someone who is a friend of theirs. Then there's the group of kids in the middle, who are doing okay. They don't feel they need the extra help, so choose to avoid it, and continue along happily. I have noticed improvements even from this.

This also frees me up to go around and better observe the participants. With the other kids occupied and receiving attention, I can find the ones who need the most help. Often, the reason why they are struggling is a simple yet fundamental flaw in their technique. I can now spend the time watching and talking with them, that previously I had not been able to do in such big groups. A simple adjustment; "bend your knee like this" or "try to push with the fingers" and suddenly it clicks. The kid who spent six months hating PE and showing no progress, now goes home with an improved sense of motivation and self-efficacy, because they have finally achieved something. This then opens them up to so many more things. Think to the basic ball skills in sport. Imagine the activities you couldn't do if you could not stop a ball with your foot, or bounce a ball with your hand. I still remember how the world opened up to me as a kid, when learning guitar, when I cracked barre chords. It was like everything clicked into place, and the entire guitar world was open to me, because I could not do this simple, fundamental, yet important skill.

The kids absolutely love this game, and they go crazy for it. I have kept the students in their positive/negative/neutral influence colours to give you an idea of how they spread across the area during any given exercise. They are in teams of two. It works as a ladder, with the winners moving up (towards red) and the losers moving down (towards yellow). They play two minute games, and the team with the most points wins.

What happens when you get to red and win? Where do you go? Well, you stay at the top of the ladder, of course. I do have to explain this about fifteen times, even to the kids who have played it several times before.

The objective: from behind the white line, kick the ball to try and knock the other ball off the cone. Doing so is worth one point. You have a turn, then the opposition has a turn. Make sure you and your partner switch after each go. When the ball is knocked off the cone, that is a point. Put it back on and keep playing. We play for two minutes, and the team with the most points moves up the ladder, while the loser moves down the ladder. You must stay behind the white line, and any attempt to block the opposition's shot will result in them being awarded one point, regardless of whether it was on target. If the game finishes in a draw, you do one quick round of rock paper scissors to determine a winner.

Why do they love this game? It's a simple concept, and it ticks many boxes.

The game is not coach-dependent. The task is simple and the kids can get on with it.

Everybody gets a turn, so they are always included.

Every action has a consequence.

Every player can score a point.

They never play the same opponent for long enough to get bored.

In ladder formats, the ability levels sort themselves out, with stronger or weaker teams moving to a more appropriate place on the ladder to face those of a similar ability, making the games more worthwhile.

I do like things to be colour coordinated, which might not help, but it makes me feel happy.

Because of the ladder format, anyone can win. Unlike a round robin, where you have to consistently get points, in a ladder format, you can be at the bottom for the entire time, then win a few games at the end, and make it all the way to the top.

There's a clear structure to follow, but nobody telling them what to do (show them where to look but don't tell them what to see).

The rewards come quickly. Points can be scored on every turn, and teams can progress up the ladder after every game.

The constraints make it an equaliser, meaning that all kids, regardless of ability, can play, because all it requires is kicking a ball while unopposed.

Kids love the pressure and the excitement.

Nobody has to wait long before getting a go at doing something important.

Everybody can be the one to win the game for the team.

Another game they love is this socially distanced version of football.

Just like the game where you knock the ball off the cone, they go crazy for this game. If we're inside, we use benches for goals. If we're outside, we use cones. Divide the group into teams, and play one team versus another. Often the games are 2v2 or 3v3, which is a great ball:player ratio. The teams must stay in their half, as we're not allowed to play contact sport. Even so, you know what kids are like, they all tackle their own teammates. We also can't use hands in this game, not just because it's football, but because it's a pandemic, and it's a rule we have to enforce. No passing the ball to each other with hands. So we don't play with keepers, although many forget that rule and take it upon themselves to assign themselves as goalkeeper. What's more frustrating is when kids manipulate the ball on the ground with their hands, and then shoot with their foot. I point out to them the use of hands, and they innocently proclaim that they didn't use their hands, that the ball was shot with the foot. The genuinely struggle to grip the fact that they just used their hands before that, which is a) against the rules of the game, and b) against the school rules for covid guidance. They cannot get why what they just did was a problem.

The games are high scoring, so we play first to three, winner stays on, and even tournaments, depending upon the number of teams. With reduced numbers in school due to the pandemic, as I keep mentioning, there are far less students in attendance with challenging behaviour. I have kept the colours consistent in the picture above. See how it is much harder for any negative influencers (yellow) to have a detrimental affect in this type of game.

Another big observation from all this is that the girls are now really coming out of their shells. We've even decided to start a girls only after school football club. With there being less boys, less troublemakers, receiving more individual attention, and playing games that are more friendly to the novice, they have started to enjoy it. It's really encouraging now to see their excitement. Without the direct opposition to overrun weak players, they actually now get time on the ball. In a proper match, the low skilled players would be blitzed by the other kids, taking the ball from every bad touch, anticipating every loose ball before them, and being faster to everything. That's why before I called it an equaliser. These constraints have manipulated the exercises into forms that are more friendly to all participants.

There are still plenty of arguments. Boys take all the turns. The boys want to win, and don't mind if not everybody has an equal amount of turns, because what's more important is that the team wins. Girls want things to be fair and equal, and would rather they all had a fair go than won. The boys get into arguments over whose ball it is and whether it was a point or not. The girls argue over somebody taking someone else's turn. I think there's room for both, and sport is a great vehicle for life lessons. Don't hog all the goes, but at the same time, if you can play quick and score, do it.

Several times, when the numbers have been right to do so, I have split the boys and girls into their own games, letting them compete separately. Due to the priorities noted above, there are far less arguments. Boys want to get the ball and play, because winning is the most important thing, and if we can get the ball quickly and shoot before out opponent is ready, we will score a point. Who cares whose turn it is? In that moment, based on the pictures the game was presenting, it was more appropriate for that kid to shoot. The girls miss opportunities to punish such disorganisation in their opponents, because they are trying to figure out whose turn it is, or they are waiting for that person to come and get the ball in order to have their turn.

Here's a basketball game that we play. Two groups, everyone competing as individuals. One ball each (those are the coloured circles each student has). Notice how, again, the negative influencers have their influence diminished. Three cones (red, yellow, blue) and a basketball hoop (black). Students have a number each (one through six) and take it in turns to shoot. They receive one point every time they score a basket. When a student scores, they move to the next cone (in a clockwise pattern). When a student misses, they join the back of the line they are already in. If a student scores, however, they get to take another shot immediately, from the next cone. Score, keep playing. The first to get ten points (or whatever number) wins the game. You can have a group winner, a class winner, a boy and girl winner. Split it however, based on the dynamic of the group.

This one we've been calling the levels game. Start at the front, work your way to the back. Each cone represents a level, becoming more difficult as the student progresses, as the shots increase their distance from the hoop. Students take it in turns to shoot. Adapt the distances to the ability of the class, and include more or less levels as needed.

Why is this one so popular? Again, simple concept, with the individual shooting being alone to do so. Just like in the others, the lack of direct opposition acts as an equaliser. If we were playing a real game of basketball, the weaker players would not get the ball, let alone be able to shoot. They get a few seconds in front of the hoop to compose themselves, which would never be afforded to them in a real game. This includes everyone in the competition, in a way that a match wouldn't. Typically, I'm all for playing games, but remember that there are a wide range of motivation levels and ability levels within this group. Playing a game might be too complex for some of the kids, and also too challenging.

The above represents the different motivation levels to participate in physical activity of all the students. Some love sport, some hate sport, some will do it if it is something they like, some are very temperamental. Where does the teacher pitch the lesson? How do you incorporate everyone into the activities?

In a sports team setting, there are less kids, and their motivation ranges are within a much narrower band. There's usually a clump together somewhere that determine the motivation levels of the team, making it far easier to not only pitch the session, but also incorporate everyone, because there are very few kids on their own as outliers. In the example above, most of the group is on the higher end of the motivation spectrum, with just one player by themselves in the lower end. Over time, we'll find out that this is not the right team for that kid. Perhaps they signed up because their friends did, or their parents have delusions of grandeur. Perhaps you're a team that trains three times a week, and the other kids love it, but this one kid is probably more of a once a week kid.

Still, I have kept the colours of the influencers in the above example. Chances are that you will have less negative influencers in team sports that require payment and commitment, because of two factors, that feels a bit chicken and egg to me; 1. Sport teaches life lessons, so exposure to these environments is likely to help a kid grow and mature, so they stop being a negative influencer. 2. If the kid is a troublemaker, the parents are less likely to bring them back for more sport. It also sheds some light on the dynamics of team sports, and how negative influencers may infiltrate, or how they may be stopped by circuit breakers.

Now to factor in ability.

Remember that green is the positive influencer kids, yellow is the negative influencer kids, and red are the neutrals. Where is the average? Where do the kids congregate? Where does the teacher pitch the lesson? The greens will help drag the lesson up, while the yellows will drag the lesson down. Their mass is larger, with the reds being like dust floating through space, being pulled in different directions by the gravitational pull of the influencers. Having just one or two good kids, or one or two bad kids missing from a lesson can make a profound difference to the makeup of the group. Each class is very different.

This lesson, for example, would likely go terribly. Just by adding a couple yellows and taking away a couple greens, the scales have been tipped massively in favour of the negative influencers. Even though ability and motivation levels are scattered similarly to the previous example. The negative influencers are more likely to interact with a whole bunch of other kids, it's hard to prevent their influence. There are not enough greens to act as circuit breakers.

The negative influencers can be highly skilled and highly motivated to participate. That isn't always the problem; lacking skill and motivation. It's more that these are the argumentative antagonistic types. They are rude, loud, like to provoke, will make fun of others, will distract and interfere. Session terrorists. In these types of environments, players of similar ability seek each other out. When I tell the class to get into groups of four, some may pick along friendship lines, while others may pick based on ability. Often the two overlap, as being good at a sport shows a common interest upon which friendships are based. Looking at the kids in the high ability - high motivation quadrant, there could be lots of different combinations of influencers in a group of four.

Ability and motivation are somewhat linked. That's why there are no extremes such as high ability and low motivation, or or low ability but high motivation. People like what they are good at, and they get good at what they like. If we were to draw a line to loosely correlate the group, it would run diagonally from the bottom left to the top right. Their motivation levels can also change on the day, based on a whole range of factors; if the kid has already been in trouble today, if the lessons have been strenuous, if there have been friendship arguments etc.

The above would be a great class to teach. There's so many good kids (positive influencers) and they are spread out at different levels of ability. They're likely to group with negative influencer kids in group work, outnumbering them, and numbing their influence. Their dense mass will also influence the neutrals (reds) to behave better, and therefore be more resistant the negative influencer kids.

Apply this to a sports team setting, and with half the numbers, we get something like this. Closer to each other in ability, closer to each other in motivation, easier for the coach to know where to pitch the session. The effect of less than half the kids coming into school during this lockdown means that the group dynamics within the class are starting to look more like this, like a team sport setting.

Now what I've done here is draw in the connections between learners and the teachers. The green lines are positive influences, the yellow lines are negative influences, and the blue lines are what the teacher can influence. With the negative influence being stronger than the positive influence, the teacher and the positive influencer students are massively outgunned. The above can also represent positions on the play ground. There are some neutrals (reds) who don't stand a chance, because they are not interacting with the teacher nor any positive influencers. This is what converts the neutrals to behave negatively.

Apply the same thinking to a situation with less kids, less negative influencers, and a second teacher, and we see now that the negative influencers stand no chance. Every neutral is interacting with one teacher and at least one positive influencer. The odds are now massively stacked against the negative influencer, and learning can now take place. With no negative influencers to bounce off of, some of the negative influencer students become neutral, or even become positive influencers, as the see that it is good behaviour that is being rewarded. Remember that kids are connection seeking, not attention seeking. Sport is largely a social experience, and everybody wants to belong. Without enough positive connections, and with a lot of time being idle, the negative influencers are in their element, causing all sorts of trouble.

Every teacher and coach probably already knows this about group dynamics. That's why they have seating arrangements and class behaviour policies. The problem I have with it all is that negative influencer students don't change, they're just simply managed. It's like we're resigned to the fact that this kid is a dick, and we need to minimise their dickitry on a lesson by lesson basis, with very little being done to course correct that child. Do we have the resources to do it? Is it our responsibility to do it? Can we work with the parents? Is it even possible to change these kids? I dread what it will be like when these kids come back to school after having been out for a couple of months. They will be behind, and full of pent up energy. They will feel like they have missed out, like they're not included, and will have a couple of months of dickitry to make up for. It's no secret that they are learning their negative behaviours in their home environments, and that's where they're being reinforced, so it is likely they will come back having regressed on that front.

Realistically, this is why we see seating plans in the classroom, and predetermined groups for group projects. It always seems like we're relying on the good kids to pull the rest of them through the class, and hope for the best. Isn't that a metaphor for life? Is it fair to do it that way?

There are plenty of times that we have received noise complaints. Several teachers have poked their heads through the door and reprimanded the children for being too loud. It does get loud, definitely. They scream and cheer when they are successful, and exclaim with disappointment when they fail. As a quiet person myself, I don't get why so many kids can't use their inside voice, especially on rainy days when we are inside. It just seems indicative of the way PE is viewed by many teachers, and the way school is viewed in general. The kids are happy, that's why they are making so much noise. It is exciting and exhilarating. Many of these kids are very quiet in other circumstances, and have really come out of their shell.

Having seen some of the teacher lead attempts at PE at the school, I can see why mine trigger such excited responses from the students. The biggest factor is autonomy. The other teachers aren't sports specialists, and many have a disdain towards physical activity. It's stretching, lines, prescribed learning, lectures, repeat after me, copy this, stand there. They do boring, repetitive tasks, with little to no interaction with each other or their environment. They are robots following their programming.

I had wondered before why the kids seemed overly excited when I showed up. The exercises we did were basic. I have so many better ones in my repertoire, but the restrictions meant they stayed there. Then I realised a couple things. The vast majority take part in little to no sport outside of school, and the ones who do, likely have terrible coaches. That shows in their agility, balance, and coordination. And also, because the PE they have received from others has been lacking the aspects that make PE fun and engaging. It felt like seeing Amish people being mesmerised by basic technology. Or American parents being impressed by seeing someone do ten keep-ups.

There's a rough checklist to use for sessions. It can vary depending upon the sport and the group, but typically follows something like this:

-Everybody is involved.

-Minimal waiting around (idleness).

-Autonomy.

-Relevant challenges (appropriate for their ability level).

-Punishments and rewards via the game (winners, losers, points to be scored).

-Competitive.

-Increasing difficulty, like levels on a video game.

-Enough repetitions to improve.

-Not too repetitive to become boring.

-Moving from one activity to the next before it becomes boring.

-Being able to interact socially.

-Receiving individual attention from the teacher.

-Learners can go at their own pace without affecting others.

-Intellectually stimulating (they have to think and figure things out).

Do the kids actually think it's worth doing? When you show them an activity or a challenge, are they looking at it, and fancy having a go themselves? I bet you can't... how many can you... can you do this?

I've waffled enough. The biggest difference, and by far the most positive, is that girls are now way more involved. So many, across all the year groups, seem to be PE resistant. They hide, they pretend to hurt, they avoid sweating or breathing heavily. One or two are still doing that, even now. But the rest are joining in, giving it a go, realising it's actually quite fun, and they're improving. Some of it is due to being able to receive proper attention and guidance from me, the teacher. A lot more of it is likely to do with there being less negative influencer kids in the lessons. These kids, mostly boys (in fact, I am struggling to think of any girl across ~250 kids that I would include in that group) are loud. I mean that not just in the noisy sense. Their influence is strong.

Many of these negative influencers are like tornadoes, wandering around the playing area. A destructive force getting in the way, kicking other people's balls away, making fun of anyone who is struggling. Imagine thirty kids, all with a ball each, practicing juggling the ball with their feet and thighs. Everyone is allowed a bounce in between juggles if they need it, and only around 5% of the kids in the school can successfully complete two juggles without a bounce. The girls are already self conscious enough, and now they are being asked to perform an activity in which they have little competence. They are seriously struggling with dropping the ball, letting it bounce, kicking it, and then catching it in their hands. They find themselves a small corner of the playground where they can hide, and they get to work. Then they hear a noise. It's a boy nearby, screaming and laughing, as he boots the ball high into the air. The ball comes crashing down and makes a big "POOT!" as it smashes into the concrete surface. A couple other boys laugh, and attempt the same. The girl looks across the playground and glances at the teacher, but the teacher is busy dealing with one kid that is crying, another that is denying he deliberately tripped the other kid, even though the teacher was watching, two more kids tugging the teacher's jacket because they need the toilet, and three girls in waiting who suddenly have splitting headaches and cannot possibly continue with PE.

What hope is there for the shy girl in the corner by herself? She looks at the boys, seemingly botting the ball into the clouds, and then looks down at her own ball, which she can barely even kick. "I'll never be able to do that" she tells herself. Now the boys are being even more reckless. Without being reprimanded by the otherwise engaged teacher, the boys feel emboldened. One of them starts smashing the ball really hard at the wall. The ball bounces off the wall, and hits the girl in the leg. She yelps, and the offender laughs. "That hurt!" she says to the boy. Immediately on the defence, the boy shouts back "I didn't mean to!" Why would he bother to apologise and check if she is okay? He's never seen that kind of behaviour at home. The boy is annoyed. How dare she get in the way of his ball, and then have the audacity to be upset that it hit her, and then to actually blame him, when it was clearly the wall's fault. The boy lurks, and stews.

The girl, after calming down, composes herself and tries again. She makes a mistake. The ball comes off her toes, and shoots away from her, over to where the lurking, stewing boy is. The boy swings back his leg, and boots the ball across the playground. "Hey! That's mine!" she says. Again, on the defensive, the boy screams back at her. "I DIDN'T MEAN TO! I WAS JUST TRYING TO GIVE IT BACK TO YOU!" Humiliated, a failure who can't do a basic task, scolded, with her ball now the other side of the playground, she looks to the teacher for help. The teacher is being pestered by a student who somehow needs the toilet for the third time that lesson. The girl decides her stomach hurts, and that she needs to go inside.